Financial institutions around the world have, so far, remained mute spectators to the cloud computing industry, which has completely transformed the way businesses have gone about handling their technology infrastructure. There are several factors that influenced their decision to stay on the sidelines, such as cost, security, data sovereignty, vendor lock-in, possibility of disruption and not to forget the investment they have already made towards their IT infrastructure.

See what Bank of America CTO David Reilly told Brandon Butler, Senior Editor of Network World:

“When we benchmark the price points in the public cloud against what we’re able to provide internally – and we have years of benchmarking under our belt now – the economic delta’s just not there yet,” he says. “There’s no economic reason for us to move to the public cloud.”

He added: “”I don’t have to solve for the security questions,” that come with using the public cloud, such as where data is stored, who has access to it, whether the bank will have access to capacity when needed”

While the second part of his explanation – with respect to security – is true today and will be true in the next decade as well, the economic aspect of public cloud is only going to get better and better from here.

From the day Amazon Web Services launched, they have been slashing costs (53 times, according to their blog post). Google announced last week that they will cut costs up to 57% on Google Compute Engine in exchange for one or three year purchase commitment. And Microsoft is in the game as well.

We can’t afford to forget that all the cloud providers are just off the starting block, and that they have many more miles to run before they reach full potential. As their datacenter infrastructure and services expand, there will be plenty of room to pass on some of the benefits of scale.

If you want proof of that, just look at how AWS revenues have been increasing at double-digit rates while allowing the company to hold on to its operating margins and, at the same time, keep cutting costs. So, clearly, there will be a point in the near future when operating your own infrastructure, even a large-scale one, does not make any economic sense.

But what about the security concerns, and what if there’s a recurrence of the outage that AWS recently experienced in the United States? According to Axios, the outage cost S&P 500 companies $150 million, and $160 million for U.S. financial services companies.

This is one of the things large financial institutions fear the most. They can, of course, take a multi-cloud/multi-vendor approach to protect themselves, but that brings its own set of technology issues, and it will definitely increase the cost of their public cloud infrastructure.

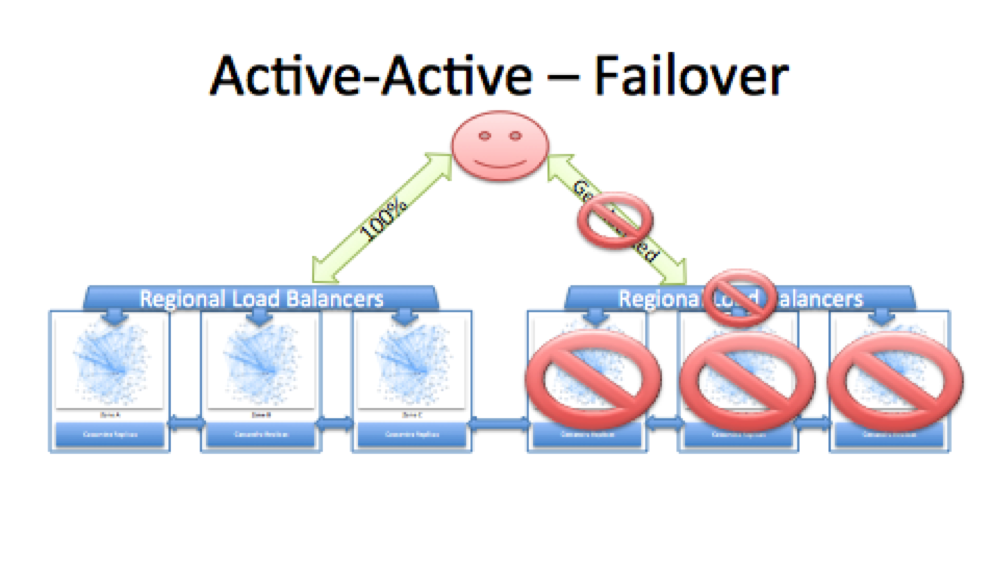

Nothing stopped all those companies that went down during the outage from having proper multi-region backups so even if a region goes down, they have another region taking over the work and serving their customers.

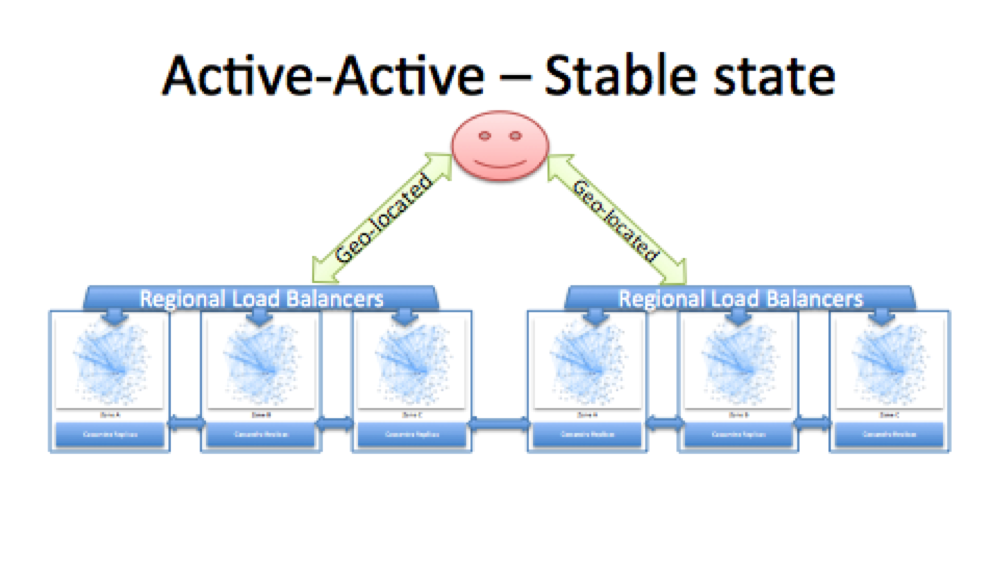

Netflix is a great example to bring into this discussion because they’ve worked hard to put systems in place that will help avoid just such situations.

Source: Netflix

But the fact that so many companies were plunged into darkness is a clear indication that businesses did not have a solid backup plan in place, and it could be because of the additional costs involved or the technological challenges – or maybe a little bit of both.

However, the cloud computing industry is evolving, and it is never going to stand still. Companies will, hopefully, have learned from the recent fiasco at AWS, and actively plan for regional failure – or possibly even for a provider failure, because it’s not an impossible task to undertake even though it might be more expensive or inconvenient.

This is not a weakness in public cloud, as some might think. If there’s technology involved, it can break at any time. The important takeaway from the AWS outage is that a plan needs to be in place at all times to cover for eventualities – even extremely rare ones such as this.

Cloud providers could, in future, make provisions for such outages. Google, for example, already offers a service called Stackdriver that allows monitoring, logging and diagnostics for applications on Google Cloud Platform and Amazon Web Services.

Why would Google go to the extent of allowing its own customers to use a competitor’s product? It’s because there is a business continuity case for it. Snap, Inc’s recent regulatory filing showed that the company is investing billions in Google Cloud Platform as well as Amazon Web Services, and this is the kind of multi-vendor approach that other enterprises would do well to emulate.

Just last week, Microsoft signed up Deutsche Borse Group as its newest enterprise customer for Office 365, while IBM migrated DSK’s banking operations to IBM’s datacenters. DSK Bank is the biggest Bulgarian bank in terms of assets and branches, with more than three million individual and business clients.

It looks like a small win in a big race, but the fact that DBG and DSK have decided to embark on the cloud ark is a clear indication that things have been set in motion for the financial services segment to eventually migrate to cloud.

There are still several challenges to overcome, and Microsoft’s and IBM’s milestones might seem like a trickle right now, but it has the potential to gather more momentum, provided cloud service providers keep pushing their own limitations in security, cost, resiliency and so on.

As the segment evolves, products will improve, things will fail and new innovations will keep coming. Such is the competition today that all cloud service providers will be racing to address the most urgent issues that are preventing large segments of companies – like financial services – from adopting cloud as the future of their infrastructure needs.

Thanks for reading our work! We invite you to check out our Essentials of Cloud Computing page, which covers the basics of cloud computing, its components, various deployment models, historical, current and forecast data for the cloud computing industry, and even a glossary of cloud computing terms.