In an interesting turn of events, it appears that FCC Chairman Ajit Pai’s whole argument for repealing Obama-era net neutrality regulations is crumbling before our eyes.

Pai’s repeated call for repealing regulations that currently keep the Internet relatively neutral seem to be based on an assumption that investments in broadband networks have declined since the regulations came into force.

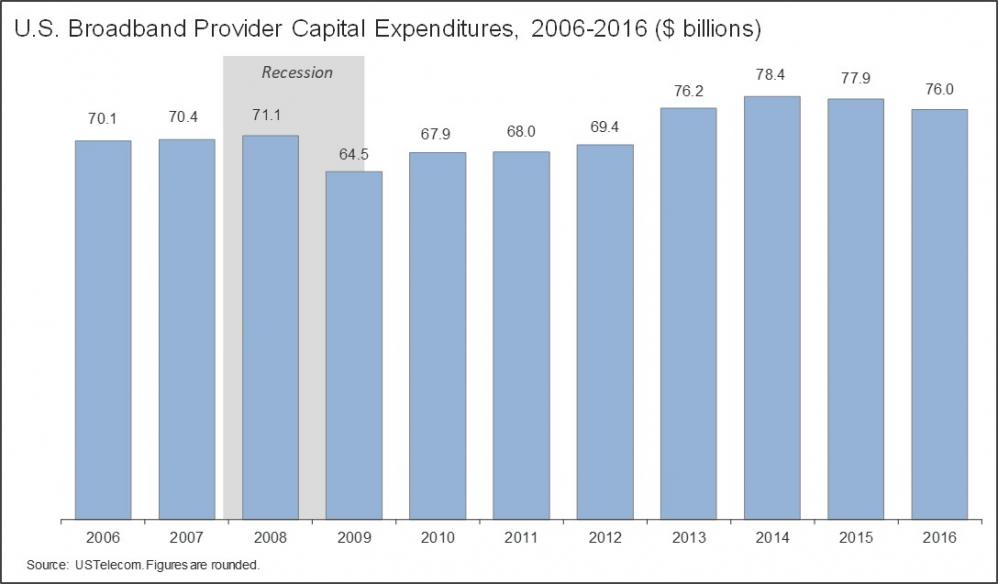

Between 2013 and 2016, however, data from USTelecom shows that capital expenditure investments by broadband providers has been relatively stable, including the period since the regulations came into effect.

That blows a big hole in what has been Pai’s loudest argument to dismantle current net neutrality regulations. The rules only came into effect in 2015, but there has been no significant stifling of investments, as can be seen from the chart above.

Earlier this year, Business Insider carried another report from consumer advocacy group Free Press, which showed clearly that investments in broadband networks have actually increased since net neutrality regulations came into effect.

That report showed that investments by the top carriers in the United States were up 5%. And when Sprint and T-Mobile were excluded (they cut investments after building out their high-speed LTE networks), that figure rose to 9%.

In a statement accompanying the report, this is what Free Press’ research director Derek Turner said:

“If investment is the FCC’s preferred metric, then there’s only one possible conclusion: Net Neutrality and Title II are smashing successes.”

If the regulations around net neutrality are repealed, it could open up the opportunity for service providers to choke or throttle speeds for web properties that are not on their “preferred” lists. That would be the exact opposite of a neutral Internet where every web property has an equal chance of reaching users.

What about “Search Neutrality”?

On the other hand, there’s Google, which controls the bulk of the world’s search traffic. Nobody knows what exact criteria the company uses to rank websites and online content. In fact, that’s the code search engine optimization (SEO) specialists have been trying to crack for years.

It’s hard to ignore the fact that even with net neutrality and Title II in place, it’s still search engines like Google, Yahoo and Bing still control which searchable content is more popular than others.

We often take it for granted that these companies are serving the best interests of their users. But the problem is, their revenue comes from advertisers, not users.

I would not assume to cast aspersions on the practices of these companies in terms of maintaining search neutrality in their individual capacities, but it’s undeniable that there’s very little transparency in how their search algorithms really work.

But we have to understand that net neutrality for Internet access is different from the neutrality of web content in the context of search engines.

Internet traffic, user speeds and such controls are the preserve of ISPs, not search engine companies. That’s what net neutrality addresses, not how traffic is directed to specific websites.

But can we ignore that large portion of the World Wide Web that is served via search engines? Hardly.

As for the FCC’s decision, it may well undo years of effort and leave the playing field open for unfair business practices. Pai hopes that the FTC will take the reins on punitive action against offenders, but that puts a very subjective twist on what’s considered “unfair” unless there is a framework of regulations governing such practices. Well, what do you know, there are! And they’re called Net Neutrality and Title II!

The focal point of the FCC-Net Neutrality argument is whether or not it’s unfair for ISPs to favor some web applications and services with higher speeds and cheaper data costs. Most of us agree that it is. But the broader picture should also include how web content is ranked and served to us on a platter by search engines that pretty much control the world’s content, whether that’s news articles, videos, imagery or other media.

If it is unfair to favor one web application over another, shouldn’t it be equally unfair to “suppress” one content provider’s output in favor of another’s, all else being equal?

+++ + +++