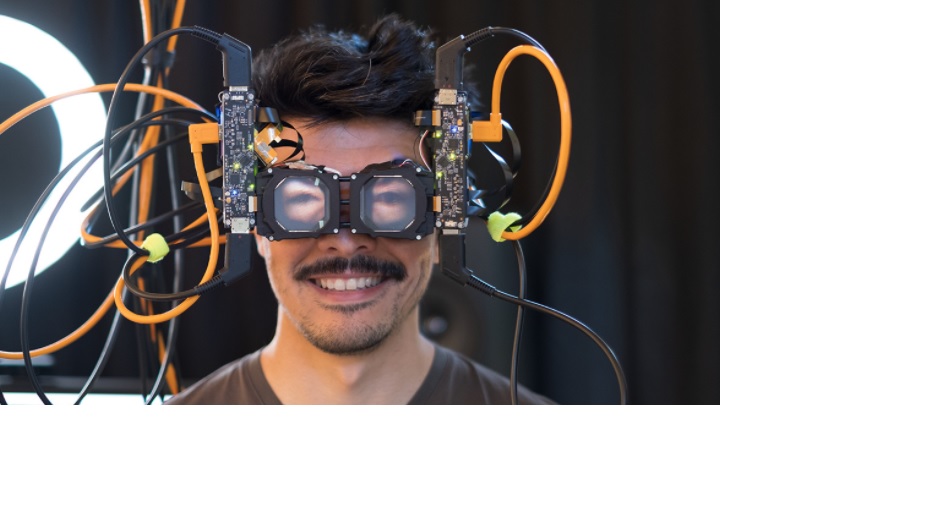

Although the results are somewhere in the middle between slightly uncomfortable and horrific, Facebook Reality Labs aims to make it easier for others to see your eyes when you’re immersed in virtual reality. An article in this week’s issue of FRL describes a technique called “reverse passthrough VR,” which is intended to make virtual reality headgear less physically isolating. Researchers have developed a method for projecting your face onto the front of a headset, they stated that it is still in the early stages of development.

How It Works

This technology is referred to as “Passthrough VR” when a headset feature displays a live video stream from the headset’s cameras, allowing users to see the actual world while still wearing their gadget. For instance, Facebook’s Oculus Quest platform provides users with a passthrough stream whenever they leave the confines of their virtual reality area. When you want to exit virtual reality quickly, this feature is beneficial. It can also be used to provide a sort of augmented reality by adding virtual objects to the camera stream. However, as noted by FRL, people close to a headset user cannot make eye contact, even if the wearer can see them fine. Bystanders who are accustomed to seeing their friend’s or coworker’s bare face may find this awkward.

Nathan Matsuda, a scientist at the FRL, decided to fix this. According to a blog post, Matsuda began in 2019, when he attached a 3D display to an Oculus Rift S virtual reality headset and tested it out. An image of his upper face appeared on the screen, and custom-rigged eye-tracking cameras captured where Matsuda was looking, allowing his avatar’s eyes to point in the same direction as his own. Instead, Matsuda appeared to be dressed as himself, with a telepresence tablet showing a duplicate of his face, which is probably just as awkward as his original appearance but with an intriguingly postmodern twist to it.

Drawbacks

Michael Abrash, the principal scientist of FRL, expressed his dissatisfaction with the proposal in a blog post, which was understandable given his background. According to him, his initial reaction to the notion was that it was “sort of a ridiculous idea, a novelty at best.” He added, “However, I do not direct researchers in their work since innovation cannot occur without the opportunity to experiment with new ideas.”

Rectification

Matsuda took the notion and went with it, leading a team of engineers to develop a new design over two years. Adding a stack of lenses and cameras to a typical VR headset display is the goal of the team’s prototype headgear, which was unveiled ahead of the SIGGRAPH conference in Los Angeles next week. The stereo cameras in the headset record a picture of the wearer’s face and eyes, and the cameras’ motion is mapped onto a computer representation of the wearer’s face. The image is then projected onto an outward-facing light field display, which is used to show information. Although you appear to be gazing through the lenses of thick goggles and seeing a pair of eyes, what you are seeing is a real-time animated replica of the original image. Alternatively, if the user returns to whole virtual reality, the display can go blank to indicate that they are no longer engaged with the outside world.

Ultimately, the outcome is a pair of octagonal goggles that would appear ideally at home in a Terry Gilliam film or television series. FRL demonstrated the system with a rudimentary depiction of a virtual face, but it also demonstrated the technology with more realistic Codec Avatars.

So What’s New in It

FRL admits that the different components of the system are not all revolutionary. For its Vive Pro headsets, HTC already offers a face tracking add-on; while it maps movement onto an avatar inside virtual reality rather than an outward-facing screen, the idea is the same. This week’s study examines the possibilities of light field displays, as well as the system’s ability to improve in-person social connections through engagement.

HoloLens-style projection glasses, on the other hand, theoretically leave your face much more precise than passthrough displays — but many of those glasses have darkened lenses, and as Road to VR points out, projected light on clear lenses can also cause your site to be blocked. However, the latest research from Facebook indicates that while firms like Apple are allegedly experimenting with passthrough designs, solid screens aren’t necessarily a barrier to eye contact, at least not in the traditional sense.