Tesla has a mountain of debt. It will look like a small mountain if you think Tesla is going to keep doubling its revenue frequently over the next ten years. It will look like Mount Everest if you think Tesla is going to be bankrupt.

Either way there is debt. On June 30, 2018 Tesla was carrying $9.51 billion in the form of long term debt. Add $2.020 billion which is the current portion of Tesla’s long term debt and capital leases, you are looking at a nearly $11.53 billion mountain.

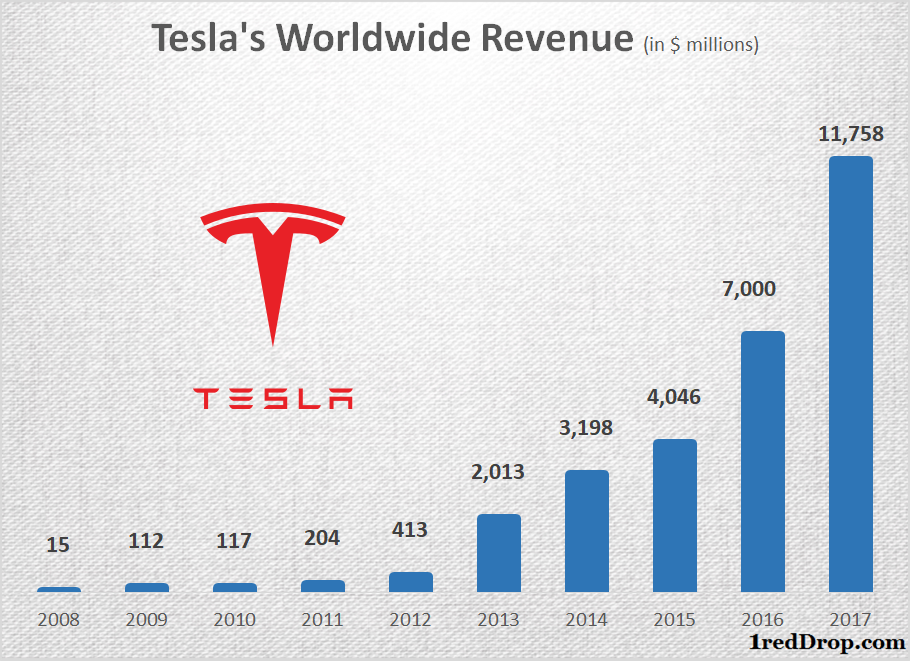

Tesla is leveraged. But that’s the way the company has gone about its business for the past several years, raising debt and equity to fund their expansion spree. But Tesla is a growing a company, and revenue has gone from $204 million in 2011 to $11.758 billion by 2017. Tesla was building around 100,000 vehicles in 2017 and, if things go according to plan, Tesla may end up easily doubling that count in 2018 and triple it by 2019.

The company has been talking about plans to reach a million cars around 2020. A ten fold increase in volume, which is certainly going to increase Tesla’s revenue many times over what they brought in 2017.

If Tesla wants to reduce leverage, all they have to do is stop adding more debt, as they watch their revenue get dragged up by accelerating production volume.

Why pay off debt? Makes no sense. That too for a company that wants to build Gigafactories all around the world.

CFO Deepak Ahuja said this during the second quarter earnings call: “we’re executing on an operating plan that keeps us sufficiently self-funded despite our CapEx needs and our debts maturing, and still keep a very healthy balance on our balance sheet.

Elon Musk followed that statement by adding, “Yeah, our default plan is we pay – we start paying off our debts. I don’t mean refinacing them, I mean paying them off.” He added, “For example, there’s a convert that’s coming due soon, a couple hundred million, $900 million, something like that. We expect to pay that off with internally generated cash flow.”

Elon wants to pay of the $900 million convert that’s becoming due soon with internally generated cash flow. He is saying Tesla does not want to re-finance debt, but pay them off with internally generated cash flow.

That’s as wierd a statement as you can hear from a CEO who is planning to more than double weekly production capacity from 7,000 units to around 19,000 units in two to three years.

Triple your production in three years and use your cash flow to pay off debt that is getting smaller on its own, relative to your revenues, when it can be used to fund your expansion? Does not make much sense, does it?

According to a research paper written by Brad A. Badertscher, University of Notre Dame, Dan Givoly, Penn State University, Sharon P. Katz, Columbia University and Hanna Lee, University of Maryland:

After controlling for factors identified by past research as affecting the cost of debt (including firm fundamentals, bond characteristics, the firm’s information environment, as well as the endogenous nature of the choice of being public), the cost of debt is higher for privately-owned firms compared to publicly-owned firms.

Specifically, after these controls, the yield spread is higher on average by more than 100 basis points (with the exact amount depending on the test specification).

Private Ownership and the Cost of Debt: Evidence from the Bond Market

The research paper covered extensive ground as the Professors looked into 256 private equity and public debt firms and 3,415 public equity and public debt firms, which represent, respectively, 1,150 and 29,193 firm-years over the years 1987-2010.

So the yield spread is higher by one percentage point on average. If Tesla’s Cost of debt increased by two to three percentage points when it goes private, Tesla will have to cough up an additional $1.15 to $1.75 billion dollars in interest payments for holding $11.5 billion debt over the next five years. That’s building a Gigafactory 4.

Even if Tesla decides not to increase its debt after going private, Tesla will have to set aside billions of dollars for interest payments.

But a sharp rise in interest payments is only a small pain in the bigger scheme of things. The real pain comes in the form of equity dilution for a private company.

Let’s assume that you are an investor reviewing companies to invest two billion dollars. You finalize two companies, Company A and Company B. All things are equal and the only difference is Company A has $11.5 billion debt and Company B has zero debt.

For the two billion dollars you are investing you will ask for more stake in Company A than in Company B. Thanks to the debt load, Company A increases your risk and you ask for more reward in the form of additional stake.

Debt increases the rate of dilution, apart from increasing interest payments.

Not a great place to be if you are the founder with 20% stake. Better to pay off the debt and reduce the rate of dilution at each funding round.

Need more proof?

“Furthermore, with over $1 billion in cash reserves and no debt, the company is in a financially strong position and is well positioned for future growth.” – SpaceX CFO Bret Johnson told Quartz in 2017

Elon Musk is running a private company with no debt. But Why?